Link to the EHT Team - Great video explanation

Office: AP&M 3351E

Office Hours: Tuesdays, 11am-12pm

What is a morphological analysis?

How does one conduct an analysis of data?

What deadly assumptions can lead me astray?

A fun example!

What does a good morphological analysis look like?

Description: What’s going on in the data?

How is this language accomplishing this linguistic task?

What is the relationship between form and meaning here?

Prediction: Does the analysis you’ve posited accurately predict new data?

Can it generate new grammatical forms? Does it generate only grammatical forms?

This is a formalist, generative approach

Explanation: Is your analysis explicable or explanatory in terms of how morphological systems usually are?

Is there any element of nature which can explain the data patterning in this way?

This is a functionalist approach

Don’t worry about the last two for LIGN 120 assignments!

Most problems involve answering a question like ‘How is ____ coded or marked in this language?’

“What is the process by which speakers mark something as ____?”

Sometimes, this is stated explicitly, but not always

Along with their ‘glosses’

You must be able to describe the patterns in the data

You must be able to account for all of the forms

Be able to identify the morphemes and what they mean

Be able to describe how they’re joined together

Be able to describe which allomorphs show up when

You must explain how your analysis is correct

Part of the task is teaching your colleagues how the system works

Explanation is an important part of your analysis

You will not get full credit for turning in a bare list of morphemes, glosses, and rules

(If you find another way you’d like, that’s great too! This is to get you started.)

| kahea | ‘eye’ | kahe | ‘eyes’ |

|---|---|---|---|

| bitia | ‘bead’ | biti | ‘beads’ |

| kĩa | ‘cassava tuber’ | kĩ | ‘cassava tubers’ |

| kahea | ‘eye’ | kahe | ‘eyes’ |

|---|---|---|---|

| bitia | ‘bead’ | biti | ‘beads’ |

| kĩa | ‘cassava tuber’ | kĩ | ‘cassava tubers’ |

| kahea | ‘eye’ | kahe | ‘eyes’ |

|---|---|---|---|

| bitia | ‘bead’ | biti | ‘beads’ |

| kĩa | ‘cassava tuber’ | kĩ | ‘cassava tubers’ |

| ### 3) Within those groups, look for recurring patterns of form |

| kahea | ‘eye’ | kahe | ‘eyes’ |

|---|---|---|---|

| bitia | ‘bead’ | biti | ‘beads’ |

| kĩa | ‘cassava tuber’ | kĩ | ‘cassava tubers’ |

| ### 3) Within those groups, look for recurring patterns of form |

| - “Weird, it looks like every singular form ends with /a/” |

|

kahe |

‘eye’ | kahe | ‘eyes’ |

|---|---|---|---|

|

biti |

‘bead’ | biti | ‘beads’ |

|

kĩ |

‘cassava tuber’ | kĩ | ‘cassava tubers’ |

| kahea | ‘eye’ | kahe | ‘eyes’ |

|---|---|---|---|

| bitia | ‘bead’ | biti | ‘beads’ |

| kĩa | ‘cassava tuber’ | kĩ | ‘cassava tubers’ |

… but you are in grave danger!

It’s usually not that easy, and you might accidentally make one of…

kĩ ‘Cassava Tuber’ (S. Barasano)

entregarse ‘To give up’ (Spanish)

on studjɛnt ‘He is a student’ (Russian)

Remember that ‘throw up’ is the same thing as ‘vomit’ (English)

Me voy a Walmart ‘I’m going to Walmart’ (Spanish)

Me gustan los gatos ‘I like cats’ (Spanish)

Mozhno li letat na samolyete ‘Can I fly on an airplane?’ (Russian)

Southern Barasano treats the plural as the ‘unmarked’ form

Many languages mark grammatical gender or noun class

Russian marks gender on verbs, but only in the past tense

Russian handles aspect by changing verbs, not adding additional morphemes

/rabotat/ ‘to work some’ (imperfective)

/pərabotat/ ‘to work’ (perfective)

Dâw (Amazonas) doesn’t overtly mark possession for inalienable relationships (e.g. your head)

Morphological distinctions can be made without adding segments

Languages can mark distinctions with tone, deletion, metathesis, nasality

Contrasts can be neutralized

Fusional languages will combine multiple meanings in hard-to-analyze ways

Spanish verb morphology is fusional

Comí enchiladas (‘I ate Enchiladas’)

Comes enchiladas (‘You eat Enchiladas’)

Carefully examine the data and determine the question

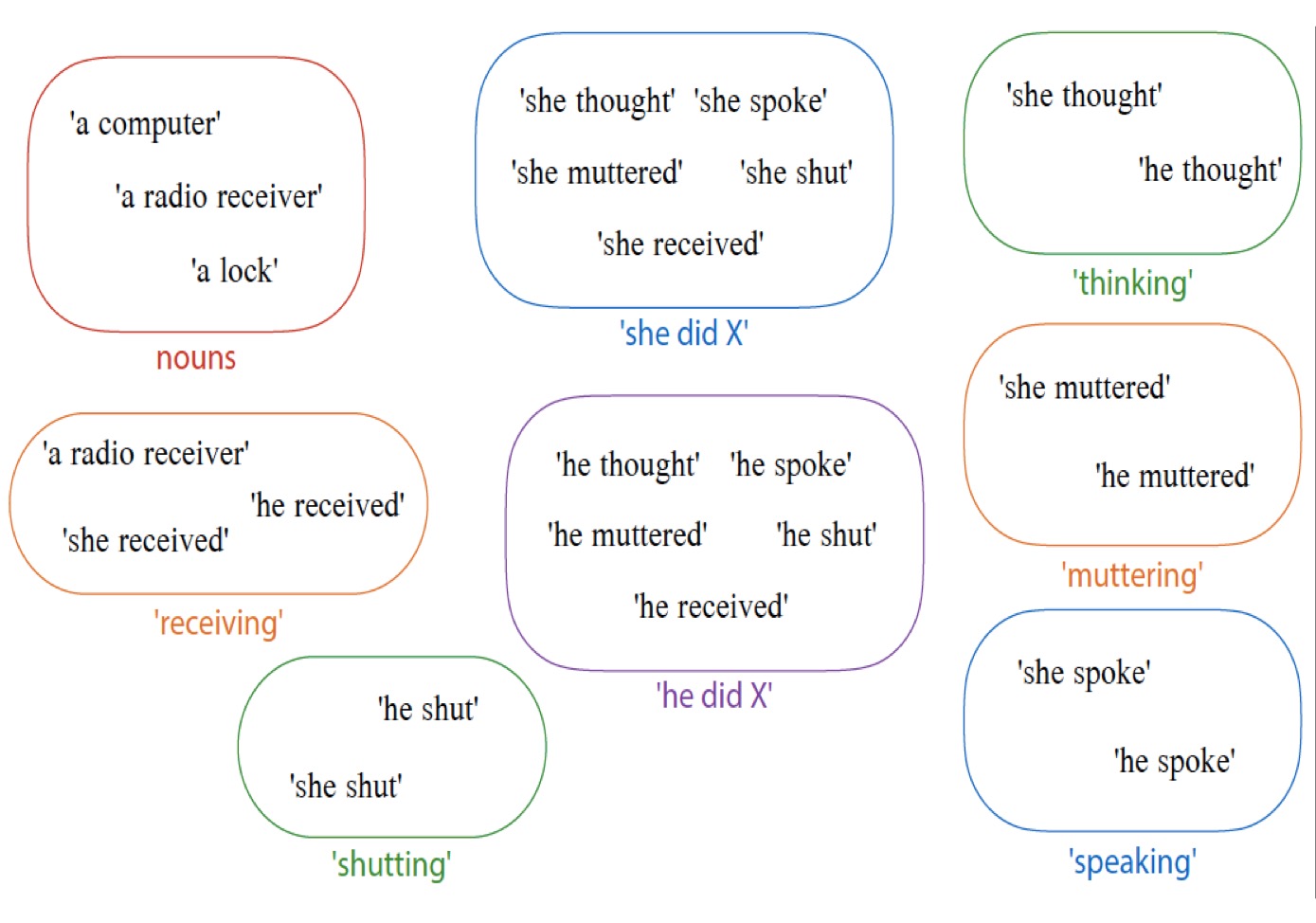

Group Data by shared elements of meaning

Within those groups, look for recurring patterns of form

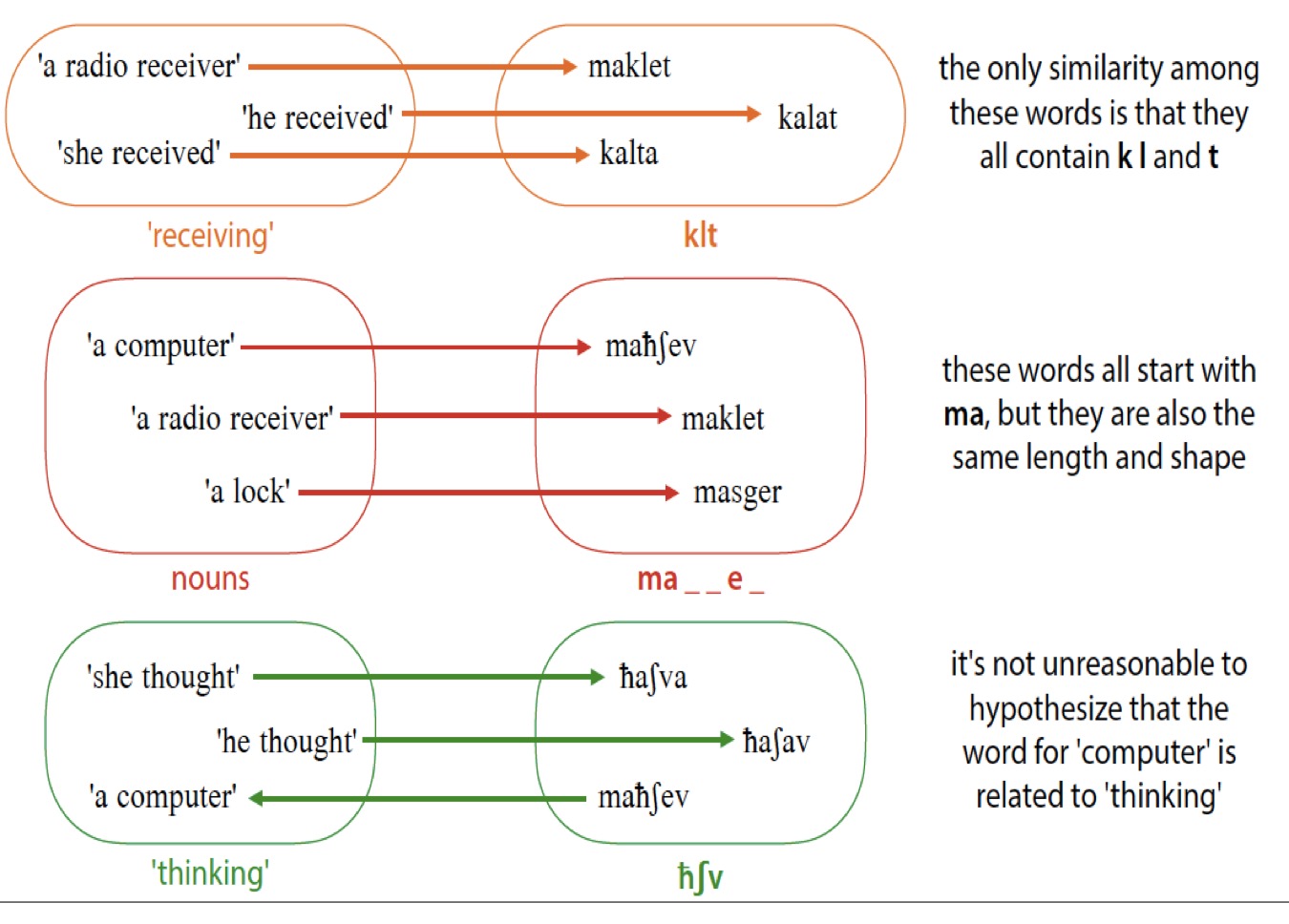

Build hypotheses about some groups, then use them to make guesses about other groups

Try to break your analysis with other forms from the dataset

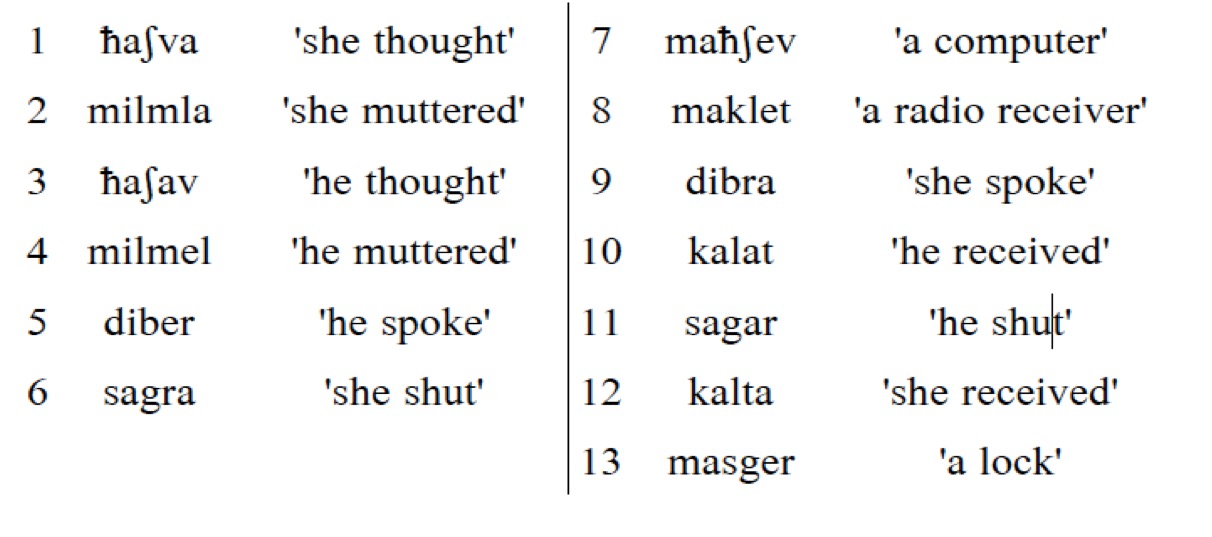

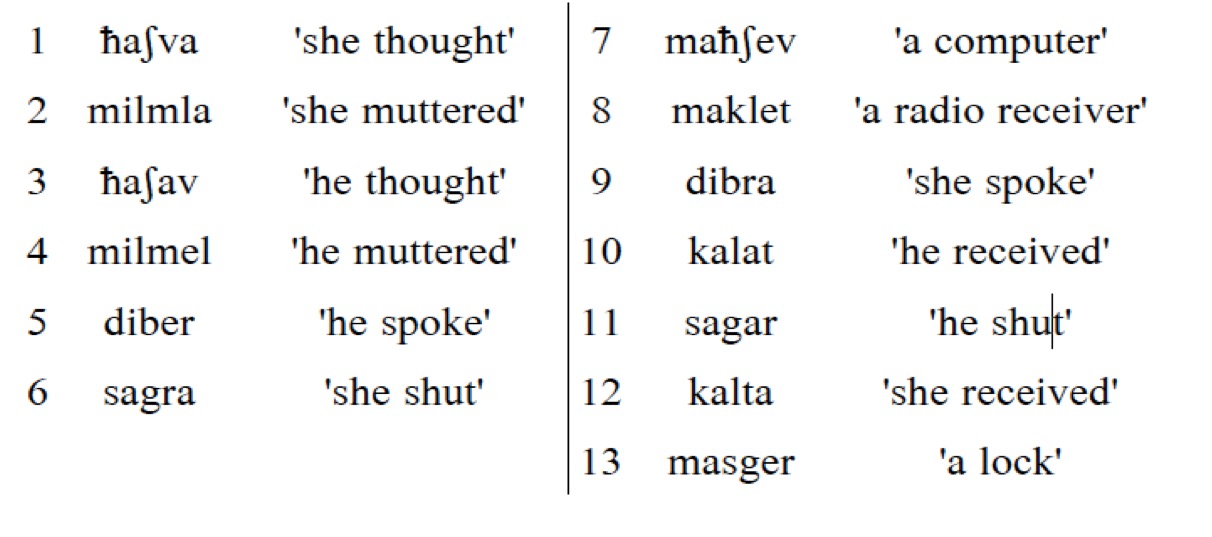

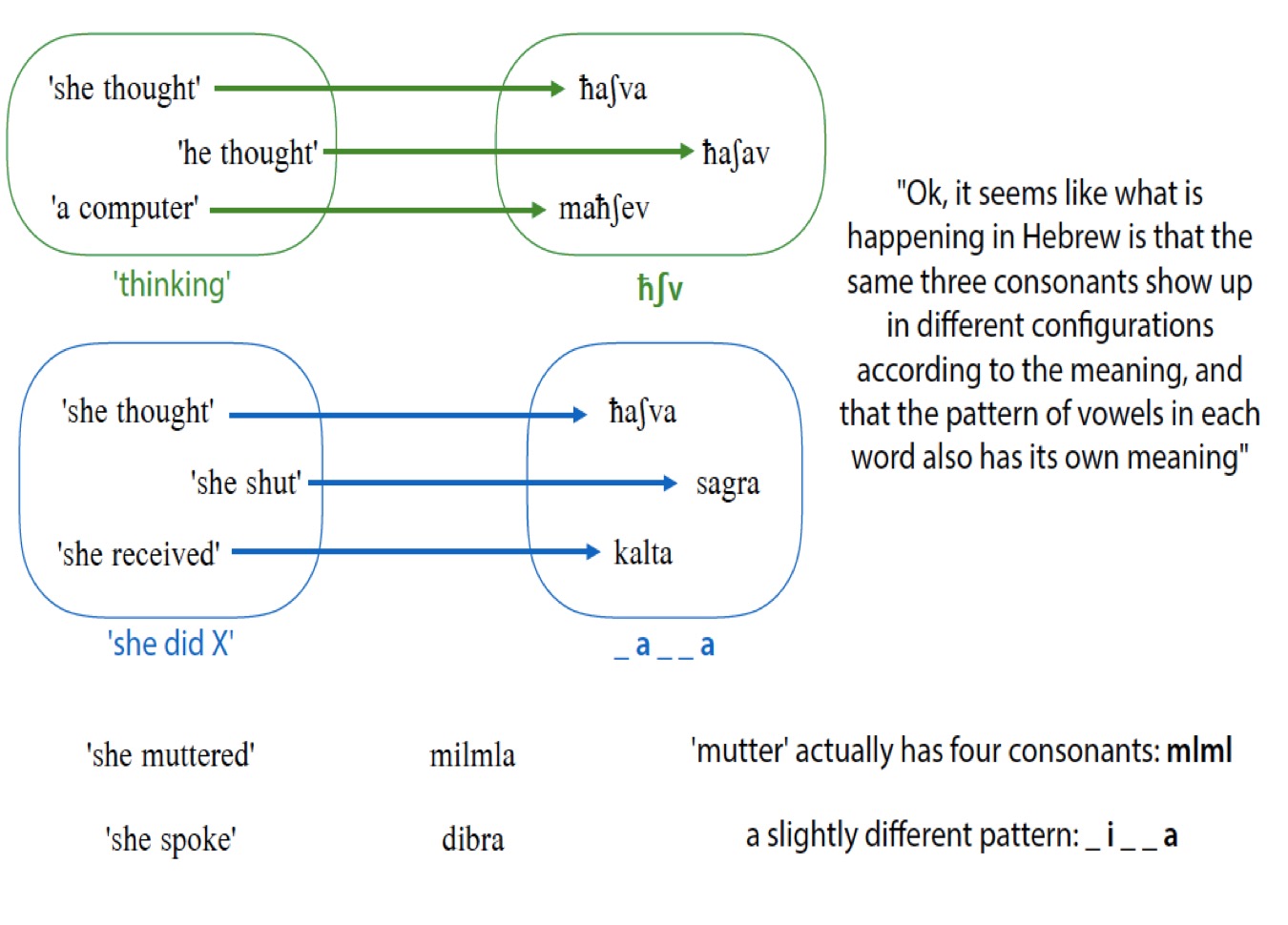

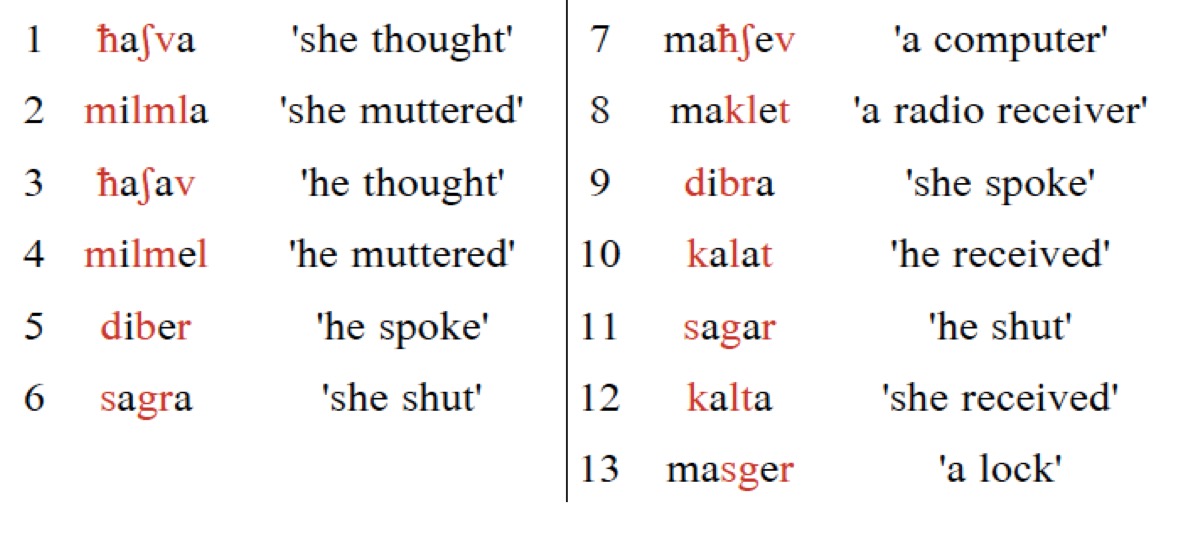

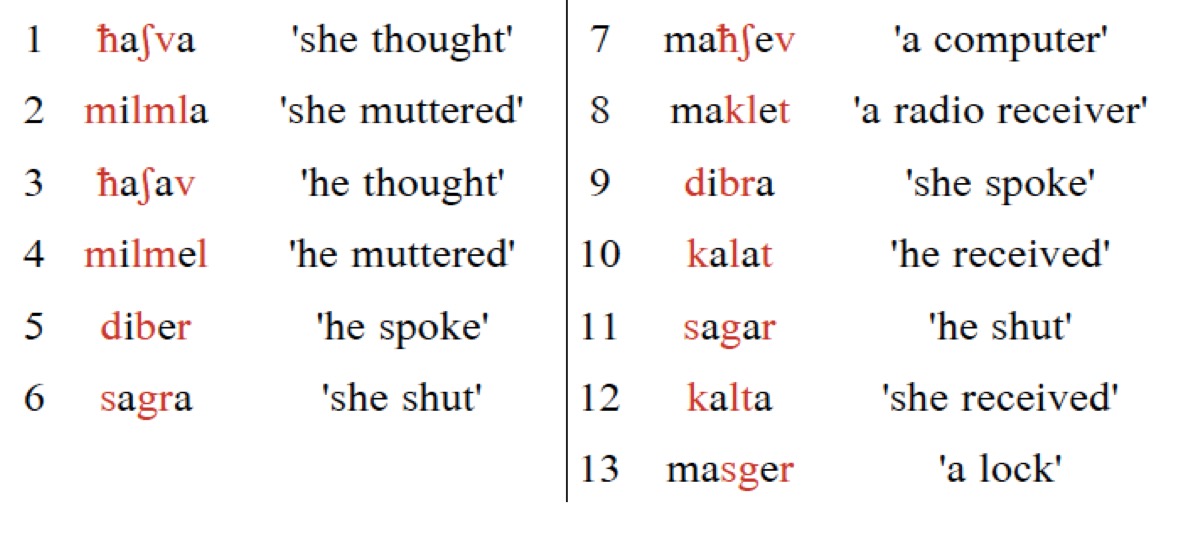

Semitic language words have ‘templates’ composed of discontinuous elements

Consonants serve as the ‘root’

Vowels mark tense, mood, aspect inflection, or fixed vowel patterns

The word’s CVCV ‘shape’ expresses other morphological meanings

Consonantal roots carry some meaning

Vowels and CVCV shape carry other types!

… but we’ve left one issue behind!

| ‘think’, ‘shut’, ‘receive’ | ‘speak’, ‘mutter’ |

|---|---|

| CaCaC ‘he Xed’ | CiCeC ‘he Xed’ |

| CaCCa ‘she Xed’ | CiCCa ‘she Xed’ |

You must be able to describe the patterns in the data

You must be able to account for all of the forms

You must be able to explain ‘How is ____ coded in this language?’

… but we want to do better than that

An elegant analysis will have a good balance of fit, complexity, and generality, while being cognitively plausible

Fit: How well does the analysis fit the data?

Generality: How much of the available data does it describe? Does it capture general patterns?

Complexity: Is there a way to handle the data which is less complex than the one you’re proposing?

Realism: Does it accurately reflect what we know of speakers’ actual grammatical systems?

An analysis which doesn’t fit the data isn’t a good analysis

Always make sure there are no words which break your analysis

This needs to come first

If you can explain every form but one, you’re probably not done

Try to write rules that account for larger chunks of the data

You’ll need to talk about lexical exceptions sometimes, but try not to

If you’re claiming every word has a different lexically determined allomorph, you’re probably doing it wrong

New or borrowed words should be adequately accounted for by your descriptions

Try to perform your analysis in a way that reflects how other languages work, too.

An analysis should be as simple as possible

Given two analyses which are functionally equivalent, the one which requires less machinery is better

Some analyses are necessarily complex, but always ask yourself if you can do the job with fewer moving parts

Your analysis should reflect a plausible grammar for the speakers

Something which requires speakers to be telepaths won’t fly

Your approach needs to be learnable

If you need to describe a new theory of morphology for a LIGN 120 homework, you’re probably off track

It won’t be a huge part of your grade

An inelegant solution is better than none at all

We understand that you’re still learning

… but do your best to make your analysis elegant

Treat the analysis as a hypothesis, then look for the data that doesn’t follow it

If it breaks down, tweak it or abandon it!

You must be able to describe the patterns in the data

You must be able to account for all of the forms

You must be able to explain ‘How is ____ coded in this language?’

Try to make your analysis optimally data-fitting, generalizable, simple, and realistic!

Morphological Analysis is the process of identifying form-meaning correspondences in a rigorous way

There are five easy steps which will help you break down most morphological problems

It’s easy to be led astray by glosses and your assumptions about how languages work, so check your assumptions

You want your analyses to be not just accurate, but elegant as well!