(I’m always chasing better learning outcomes. Oh well.)

The Wide World of Words

Morphological Productivity

Productivity as Restriction

Productivity as Extension

Lexicalization

The average adult speaker of a language knows 20,000-30,000 words

These include function words

As well as content words

These words range from very common (‘the’) to very uncommon (‘decimate’)

“In a given corpus of natural language, the frequency of a word is inversely proportional to its rank in the frequency table”

The most common words are really common!

We don’t need to know that many words to be functional day-to-day

but rare words are exceedingly rare

Because we probably don’t know all of the words

… and even if we did, we need new words regularly!

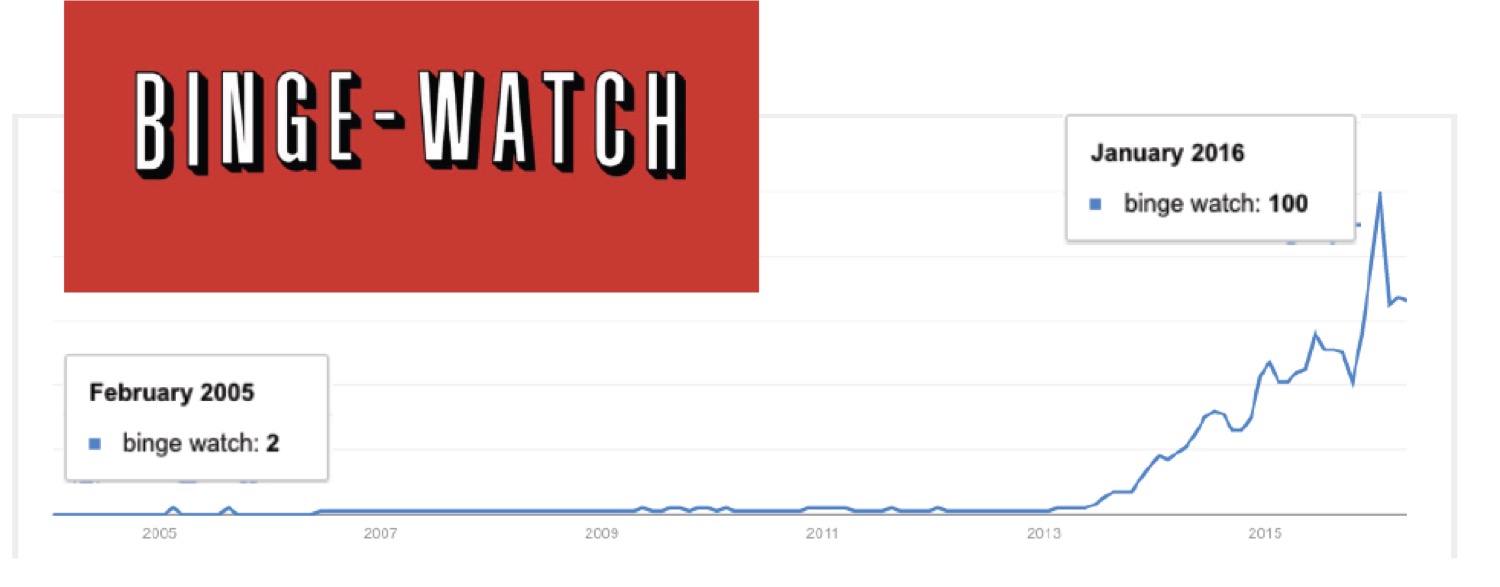

New concepts are regularly developed

New cultural or general concepts need marked

Affixation

Stem modification

Conversion

Reduplication

This could be inflectional

Or derivational

Cuteness, but *quicklyness

English plural as ‘cats’, ‘dogs’, ‘dishes’, ‘deer’, ‘oxen’, ‘foci’

Speakers know what forms apply to which words

There are two ___?

An object that is a lot like this would be ___?

If you turn something into a glanch, you would ___ it?

Somebody who uses a glanch would be a ____?

The degree to which a grammatical process is in use by speakers

Can we use this morphological pattern with a brand new base?

What knowledge or abilities do speakers/listeners use to make/understand words they haven’t heard before?

How can we characterize the productivity of a morphological process?

How do we know what processes can and can’t work with a given word?

Is this word form learned as a monolithic whole, or as analyzable chunks?

There are two approaches in common use

“Let’s assume that all morphological patterns are unconstrained, and then identify those unique places where it appears constrained!”

Identify the pattern, then describe when that pattern can’t be extended to new forms

The restrictions dictate the productivity

Sparse -> Sparsity

Secure -> Security

Responsible -> Responsibility

Productive -> Productivity

Foolish -> *Foolishity

Sexy -> *Sexity

Peaceful -> *Peacefulity

-ity works with all adjectives except those ending in -ish, -y, or -ful

Phonological Restrictions

Semantic Restrictions

Morphological Restrictions

The form of the base restricts the application of an affix

English patient noun -ee works in retiree and payee

English verbal -ize works with privatize and globalize

These have no semantic or morphological basis, just simple rules based on the form of the word!

-ee only attaches to words without final /i/

-ize only attaches when there would be an alternating rhythm

The meaning of the base restricts the application of an affix

Russian “quality noun” affix -stvo only works with people-describing adjectives

bogatyj ‘rich’ -> bogatstvo ‘richness’

znakomyj ‘acquainted’ -> znakomstvo ‘acquaintance’

udaloj ‘bold’ -> udal’stvo ‘boldness’

lukavyj ‘wily’ -> lukavstvo ‘cunning’

vjalyj ‘withered’ -> *vjal’stvo

priemlemyj ‘acceptable’ -> *priemlemstvo

The grammatical or morphological nature of the base restricts the application of an affix

The English -ee only attaches to verbs

The -ando progressive aspect in Spanish only attaches to ‘-ar’ verbs

“Let’s assume that all morphological patterns are constrained, and then identify those unique places where it appears to extend!”

Identify the pattern, then describe what forms it extends to.

The extent dictates the productivity

“English -ity is typically used to make nouns from adjectives ending in -able and -ive”

responsible -> responsibility, productive -> productivity, available -> availability, payable -> payability

creative -> creativity, inclusive -> inclusivity, responsive -> responsivity

“Sure, maybe it works with some other words, but that is where it’s always productive”

A: Almondy

B: Almondish

C: Almondtacular

D: Almonderiffic

E: of almond

Especially when many morphemes are borrowed and the ‘proper’ form depends on the language

“Was this borrowed from Latin? Greek? Is this Germanic?”

A: Octopus

B: Octopuses

C: Octopi

D: Octopodes

E: Hexadecapus

We can ask these same questions for other patterns of morphological change

How often does this process occur for new words?

How regularly (and where) does it occur for existing words?

Humans are excellent at finding and extending patterns

Let’s give it a try

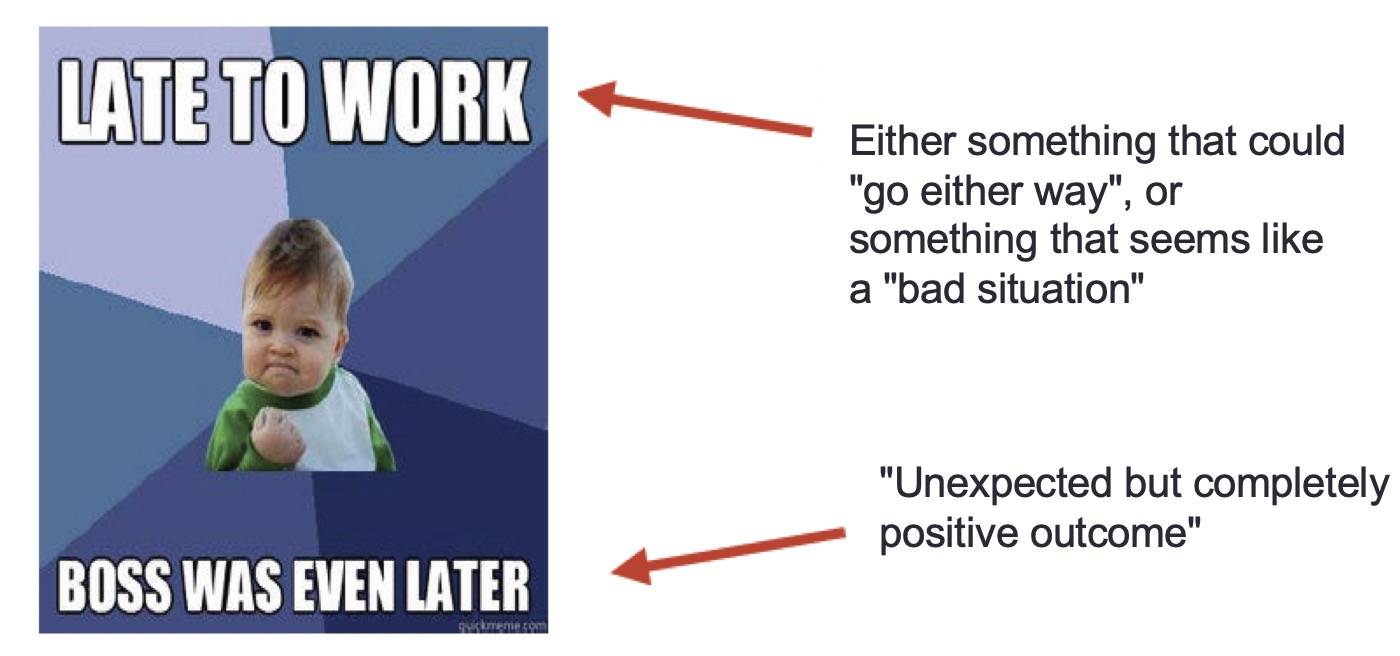

Seeming success -> Unexpected twist of fate leaving the success hollow

Keysmashing (asdf;lkj)

SpOngEBoB MemE!

-en is no longer a productive plural for English

Ablaut is no longer a productive process

We view ‘children’ as a quirk of ‘child’

We view ‘brethren’ as a separate word

We consider `strong’ (ablauted) verbs to be ‘irregular’

You may find it in old words

Speakers may be vaguely aware of the affix

It’s no longer active

It is lost to the language

… and some things that should not have been forgotten were lost. History became legend, legend became myth. And for two and a half thousand years, the morpheme passed out of all knowledge.

|

| Until, when chance came, it ensnared another bearer. |

There are a great many words, but we always need more

Some affixes are productive, available to use for new words

We can define productivity in terms of restriction, or extension

When a form completely ceases to be productive, it is lexicalized

… until it is discovered once more